В сети впервые опубликовали неизданное стихотворение Набокова о Супермене. Мы его перевели

11232

5 минут на чтение

Литературный портал The Times Literary Supplement (литературное приложение Times) опубликовал ранее нигде не издававшееся стихотворение Владимира Набокова, посвящённое... Супермену! Называется оно The Man of To-morrow’s Lament.

У произведения интересная история. В нём описываются переживания Человека из стали по поводу того, что он не может иметь детей от Лоис Лейн. Сам Набоков познакомился с комиксами о Супермене благодаря сыну, который любил эти истории. В июне 1942 года, спустя всего пару лет после прибытия в США, он отправил стихотворение редактору The New Yorker Чарльзу Пирсу. Писатель посетовал, что английский язык пока для него в новинку и потому середина стихотворения получилась «проблемной». Пирс отказал Набокову в публикации.

В итоге стихотворение отыскал в папке в библиотеке Йельского университета литератор Андрей Бабиков.

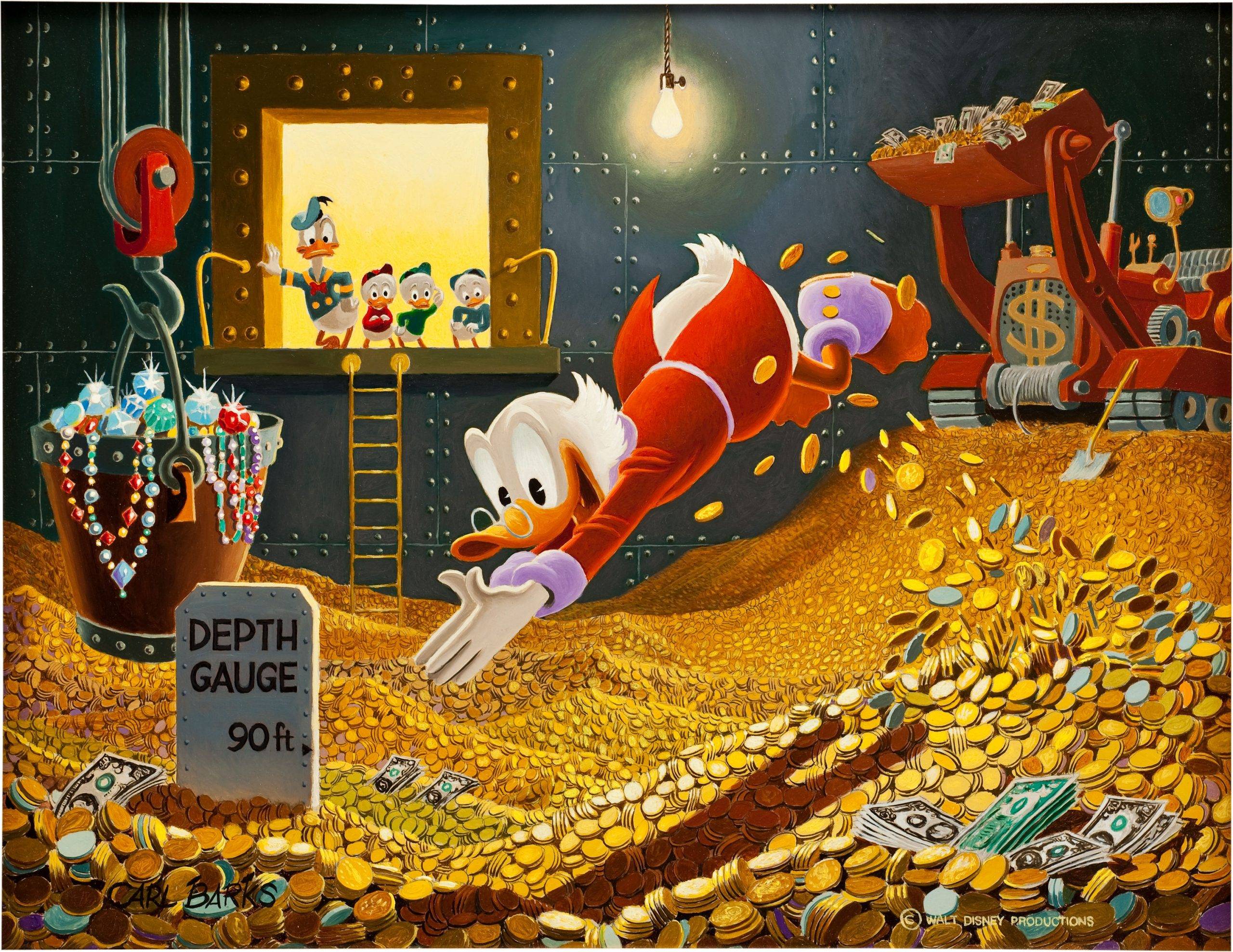

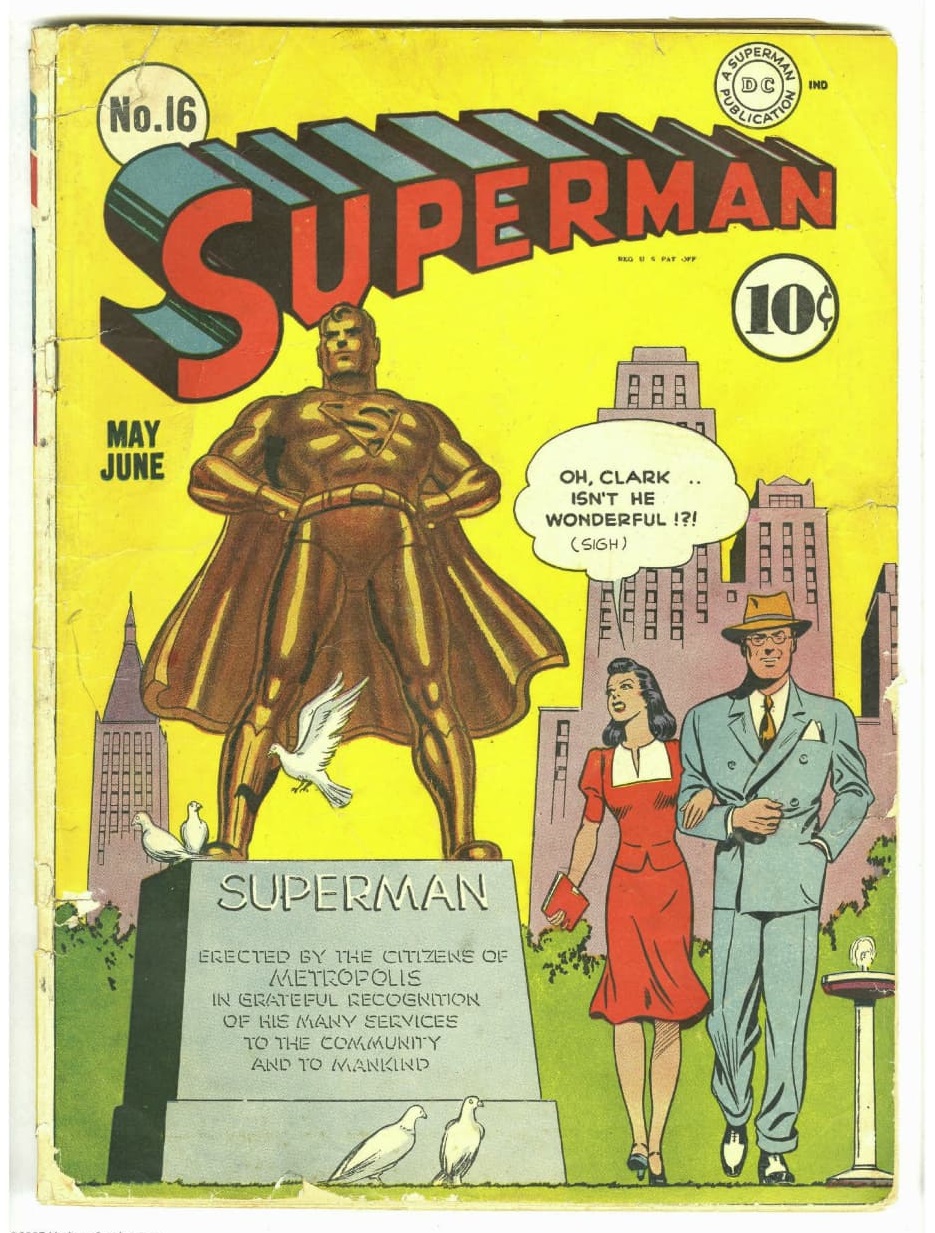

Пирс и представить себе не мог, что отказал в публикации, возможно, первого стихотворения о Супермене, которое в итоге нигде не появилось. Он также не мог предвидеть, что его автор, «написавший довольно замечательные вещи», к концу 1950-х станет знаменитым по всему миру писателем, будоражащим умы проницательных читателей и ценителей искусства, и потерянное стихотворение 1942 года станет одной из недостающих страниц его творческой биографии.Бабиков предполагает, что Набокова вдохновила обложка комикса Superman № 16, на которой Кларк Кент и Лоис Лейн в парке смотрят на статую Супермена. Писатель даже включил в произведение фразу «Oh, Clark ... Isn’t he wonderful!?!».

Андрей Бабиков, литератор

Оригинал

The Man of To-morrow’s Lament

I have to wear these glasses — otherwise,Перевод

Печаль Человека Завтрашнего Дня

Я на неё любуюсь сквозь очки,Статьи

«Люди — идиоты»: первый трейлер научно-фантастического комедии «Киллербот»

Лютоволки — теперь реальность. Ученые создали животных с ДНК вымершего волка

Один из волков попал на обложку TIME.

Герои из Apex Legends, смена погоды и режим эвакуации — первые детали Titanfall 3

Экранизация Minecraft может получить продолжение

Учитывая кассовый успех, это лишь вопрос времени.

Роботы, пришельцы и коты — тизер четвертого сезона «Любви, смерти и роботов»

СМИ: Роберт Паттинсон может сыграть антагониста в «Дюне 3»

Возможно, ему достанется роль Скайтейла.

Тони Гилрой: без малыша Йоды не было бы «Андора»

Объявлены финалисты премии «Хьюго» 2025 года

Нашлось место даже для Dragon Age: The Veilguard.

Инсайдер: ремейк The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion выйдет в апреле

Новые кадры фантастической комедии «Киллербот» с Александром Скарсгардом

Премьера 16 мая.

Показать ещё

Спецпроекты

Все спецпроекты

Все спецпроекты